How to Help Children with Higher Functioning Autism Understand Social Skills by Richard Solomon MD

Do You Celebrate Kwanzaa?

During Christmas break, Adam (not his real name), a 9-year-old with high functioning autism (HFA), came in to my office with his mom for what I thought was going to be a standard review of his educational, social, and developmental status. After we settled in, I noticed an anxious expression on his mother’s face; and Adam, normally loud and rambunctious, began to play a bit too quietly with my Thomas the Tank Engine trains as his mother spoke to me. I suspected he was in trouble for something. Sure enough, when I asked my usual, “So what’s been going on with Adam?” his mom told the following story.

The family is Jewish, and Adam had been studying religions of various types in Sunday school. Well, he became ‘obsessed’ with world religions, learning all kinds of facts about them on the internet, going well beyond what he had learned in Sunday school. He got into it; which is common for kids like Adam. But, to be honest, his parents and siblings were getting a little tired of Adam talked incessantly about Muslims, Christians, Bahai, Kwanzaa, and Mormonism and how they celebrated the holidays.

One day, as Adam and his family were walking down the street filled with people shopping during the Christmas season, Adam walked right up to a large African American man, apropos of nothing, and, in a loud voice, asked, “Do you celebrate Kwanzaa?”. His mother said ‘everyone on the street looked at us’. His older brother and sister were humiliated. She said, ‘Luckily the man was very nice, but I could tell that he was shocked when Adam out of nowhere asked him the question.’ She apologized to the man for her son’s social faux pas and the family slinked away down the street avoiding eye contact.

Adam felt bad that everyone was ‘mad at him’. He didn’t understand that what he had done was socially inappropriate. I said to him, “You didn’t want to embarrass anyone; you just wanted to find out more about the man’s religion because you were studying religion.” Adam nodded and felt much better. He proceeded to tell me all about Kwanzaa. It wasn’t a matter of right or wrong. Adam was just curious. Clearly Adam needed to understand what he did wrong, but it had to be done carefully and sensitively. I needed to understand the nature of Adam’s social faux pas so I could help him and young people like him to be more aware socially, but I wasn’t sure how to explain all this to Adam.

So, after the visit, I began to think about exactly what was ‘socially inappropriate’ about Adam’s interaction. It had to do with his developmental immaturity, no doubt and, clearly, he had not considered the other person’s perspective. This is one of the most important social skills, namely, being able to consider whether the other person is interested. But there was something gnawing at me that I couldn’t figure out, at first. My subconscious was using this incident to gain some insight about the very nature of social interaction and ‘appropriateness’.

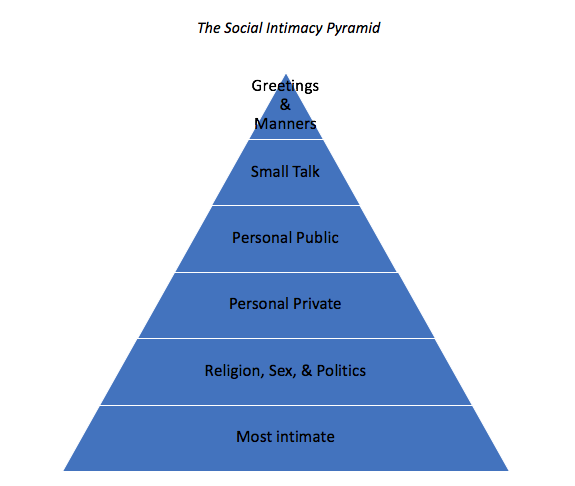

As I wondered about this over the next few days, it hit me: Adam had skipped several layers of what I will call ‘The Social Intimacy Pyramid’. He didn’t understand the social boundaries of what is considered public and what is considered private. These are the details of social consideration! In fact, I realized, he had skipped 5 layers of social intimacy and jumped right into the topic of religion! See the figure below:

The Social Intimacy Pyramid describes a set of cultural norms that people follow in any social exchange that should occur in a certain order so as not to be ‘socially inappropriate’.Here is a list of the levels with some brief advice about ways to promote understanding at each level for children with HFA.

The first level of social intimacy (which is not very intimate!) involves greetings & manners. Adam didn’t bother to say ‘Hello’ or ‘Excuse me’ to the gentleman. Learning to say ‘Hello’, ‘Goodbye’, ‘Please’, ‘Excuse me’ and ‘Thank you’ are fairly easy skills to learn for children with HFA using memorization through rehearsal. Just practice the skills—smile, brief eye contact, greeting, etc.— until they can do it without prompting. As with all the levels of intimacy, I recommend that parents always explain why these levels are important using simple-to-remember social stories. “Greetings are important because: ‘When you meet people you greet people’.” And “Manners are important because: ‘It’s so nice to say ‘please’ when you want something; and ‘thank you’ when you get something’.”

Then comes small talk. Most adults are pretty good at discussing the weather or sports or the latest shows on TV. Small talk can be an art form where acquaintances can talk for long periods without saying anything really important at all! I overheard some young school children talking small talk about their new shoes. Adam didn’t talk about the snowy day or the Christmas season or shopping for toys. He skipped small talk. I would explain to him that talking to people about what they like or are interested in is ‘the first way of getting to know about people’. Small talk is the first step toward empathy—taking someone else’s perspective. The art of small talk can be learned through daily interactions at home with children about what they did today, what they like to do, what happened with their friends, etc. Parents can also have the children memorize certain phrases that ask others about their interests like, “What do you like to do?” because ‘Don’t you want to know about other people?’ This question invokes empathy.

Then comes the public personal, sharing things about ourselves that anyone can know, like how many brothers and sisters we have or where we are going for summer or Christmas vacation. Or what we do for a living, our roles in life: Mail person, chef, policeman or woman, Bob the Builder. It’s personal but it’s public. Children can talk about their friends or what they like to do for fun. Adam did not talk about the fact that he was studying different religions in Sunday School. The public personal can spill quickly into the next level of intimacy—the private personal—where many children, not just children with HFA, start to get into trouble.

Watch out for the private personal! How many times has your typical four-year-old asked ‘Why is that man (or woman) fat’ or ‘black’ or ‘bald’ or ‘old’? Children that age (or developmental level) don’t understand the idea of ‘private’; they are just learning that you can hurt the feelings of a human being by pointing out their physical features because you are talking about something ‘personal and private’.

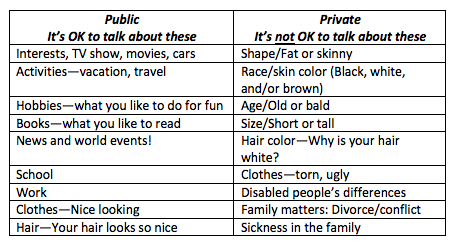

I spend the most time talking with parents and patients about the difference between the public personal and private personal. Here is where we can take a big emotional step, for all children, to talk about ‘empathy’ and how it feelsto be another person. We must help the children take a leap of both imagination and reasoning to understand the inner life of others. I recommend literally drawing a line down the page with one column labeled ‘Public’ and one ‘Private’ and talking about this critical distinction with the children and why one is OK, and one is not OK to say to others. Here’s just a sample list. There are many domains of distinction between public and private:

This list leads to important discussions. Why, for instance, can you say nice things about a person’s looks or hair but not negative things? I explore the reasons why they should care about and consider other people’s feelings. Why does it hurt people’s feelings when you talk about their bodies? These are not easy questions to answer but they can be discussed in ways that children understand.

Adam might have shared that he had been studying about other people’s religions in Sunday school and that he was assigned to ask people about their religious beliefs (public personal) and would the man mind if he asked him some private questions (private personal/religion). But he didn’t, and it was very embarrassing for his family.

Religion, sex ,and politics are at a very deep level of the Pyramid of Intimacy. You even have to be careful talking about these topics with your closest friends. Many of us can’t broach these domains with family members unless they agree with you. So, Adam skipped many levels of intimacy when he broached the subject of religion with a complete stranger on the street! I don’t really expect children with HFA to understand the complexities of religion, sex/gender, and/or politics, but parents of children with HFA should at least have a basic discussion about these topics. Adam, for instance, knew the names and belief structures of many different religions and he was happy to tell me all about them.

Finally comes the most intimate level, a level we share only with our closest friends and family members. These conversations have to do with our deepest values, beliefs, feelings, and even secrets.

Here we are talking about love and romance, health and sickness, conflict between family members, sibling rivalry, our personal problems, anxiety, depression, etc.

While children with HFA will not yet be ready to understand this level of intimacy, we can begin to recognize their deepest feelings. When I understood that Adam was just curious and meant no harm, he felt better. We must start by joining the child’s intentions and then kindly explain how, the next time, he might do things a little differently.

What if Adam had walked up to the gentleman on the streets during the Christmas holidays and said, “Hello, sir. (Greetings) The holidays are great, aren’t they? (Small talk) My name is Adam. I’m Jewish and studying other religions in Sunday school. We are taking a poll of different religions. (Personal public). Would it be alright if I asked you a personal question about your religion? (Personal private). Do you, by any chance, celebrate Kwanzaa? (Religion)” It might seem curious to a stranger to be approached like that, but I bet the gentleman would have thought Adam to be at least socially appropriate if not cute and maybe even charming.