Written by: Richard Solomon, MD

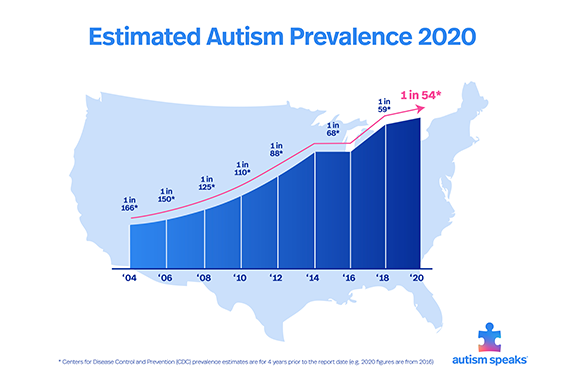

You’ve probably seen the Autism Speaks ads: “Every two seconds a child is diagnosed with autism.” As I write this today, the CDC has determined that 1 in a 54 people or 2% of males has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD)!1Ever since Bob Wright, former president of NBC, became the grandfather of a child with autism and created Autism Speaks, awareness of and research on the condition has skyrocketed. Given this prevalence, you probably know someone who has a child with an ASD.

Welcome to my world. I am a developmental and behavioral pediatrician who has specialized, over the last 30 years, in caring for, diagnosing, and helping literally thousands of children and adolescents with ASD.

Over this time, my patients and their families have taught me so much about what it means to both struggle and grow and accept what can’t be changed. I have learned to see through the eyes of the ‘differently abled’ and their families. I have been witness to the miraculous potential within many of these children and adolescents who become fully functional and even indistinguishable from their peers (click here to see Ben Gretchko’s graduation speech to his high school class). Recent research has found that the child with autism who receives intensive early intervention can ‘outgrow’ their diagnosis.2 In my practice, I have many children who, over time, no longer met the official (DSM 5) criteria for an autism spectrum disorder.

Andrew Solomon (no relation to me), in his wonderful, profound, and essential book Far From the Tree, discusses the difference between illness and identity. After interviewing hundreds of families who had a child with a distinct illness or disability, he discovered that: “Difference unites us. While each of these experiences [of disability] can isolate those who are affected, together they compose an aggregate of millions whose struggles connect them profoundly.” I fully agree. We must embrace our differences.

In my new series of blogs, I plan to explore this theme of disability versus identity, of being ‘autistic’ versus having autism, of fixing a ‘condition’ versus promoting potential, of repetition/addiction versus creativity, and of isolation versus connectedness. Of embracing differences. I would like to start this exploration by attempting to answer a puzzling question that’s on everyone’s mind: Why is autism increasing so much? My answer might surprise you, as it did me.

Since 1980 autism has increased 20-fold! As the brand-new graph (below) from Autism Speaks shows, the dramatic and disturbing rise has continued, tripling over the last 15 years.

When I speak to audiences about the importance of intensive, early intervention for children with autism, this question—Why the huge increase in autism?—is the most common. In the last decade, research has found several pieces to this puzzling question but there are still missing pieces. Over the last several years, as I saw hundreds of children with autism in my office practice, I began to notice a pattern in the family histories that led me to speculate about the causes for autism’s rapid rise. Let me start with what we know from science about the established causes of autism’s sharp increase and then, at the end, I’ll share my hypothesis about the missing puzzle pieces.

First, autism is increasing because we are diagnosing milder forms. This is reflected in the term autism spectrum disorders because it includes such a broad spectrum of children that we, in the medical profession, never would have included before. At first, only children with ‘classic autism’—no words, in their own world, and focused solely on repetitive behaviors—would have been diagnosed. Then we included children with some language but with serious problems socializing whose special interests—cars, trains, wheels, Toy Story, LEGOs, YouTube—took them out of social interaction. Now we have expanded the spectrum to include those who have normal language but who have trouble functioning in school, can’t make or keep friendships, and have dominating intellectual interests like knowing all the sports stats for the Tigers or the train schedules for the B&O. No question, expanded diagnostics is a major puzzle piece that explains autism’s increase.

Second, there is a hunt on. Our society has become sensitized. The media is making mothers hyper-aware that their children might have symptoms of autism. I recently evaluated an infant who was only 6 months old because her mother had read an article on autism’s symptoms which her child had (She was eventually diagnosed with mild autism!). In the last two years, The American Academy of Pediatrics began recommending that all pediatricians screen for ASD at 18 and 24 months2, which is a very good thing given how effective intensive early intervention can be. Some studies suggest that autism can be diagnosed reliably in children as young as 14 months. This puzzle piece fits. As we search with more sophisticated screening tools and diagnose earlier, we increase the number of very young children identified with the condition.

Third, with such big persistent increases in autism’s prevalence, most of us in the field suspected that environmental factors had to be one of the big pieces. Recent large-scale studies, however, report that the environment contributes only about 20% to autism’s increase with genetics, as the primary cause of autism, contributing 80%.3 At first immunizations and/or mercury in immunizations were suspected but 20+ large-scale and well-done studies have put that cause to rest4. Dietary causes have largely been disproventoo5. The suspected list of environmental causes is growing and includes such things as the survival of very premature babies, having older parents especially older fathers, exposure to environmental toxins like pesticides and/or antidepressant medications during pregnancy, and maternal obesity, among others. Maybe some other environmental cause will account for more of the puzzle but not so far. It’s interesting that many of these environmental factors are associated with a highly advanced society.

Finally, autism is now known to be primarily a genetic condition6. In a recent analysis of very large samples of the DNA of families who have children with autism, researchers have identified about 100 ‘autism genes’6. These genes code for the many different kinds of neuronal (brain cell) connections in the brain and when there are abnormal additions or deletions to these genes, the brain cells don’t connect as they should, leading to the diagnostic symptoms of autism. Now we know that the cause of autism is mostly genetic with some environmental contributions, but there are no other ‘genetic’ conditions that increase the way autism spectrum disorders do!

I collect three generation genograms (family trees) on all of my families as part of a good medical history. Over many years, I began to see patterns in the genograms. Not only was autism showing up in some generations of the family tree, but I noticed certain traits appearing: Shyness, social anxiety, obsessive/compulsiveness, perfectionism, neat freaks, the detail-oriented, rigid and/or orderly, collectors and hoarders, gamers and fanatics. Traits are inherited. How relatives think gets transmitted! Then I began to notice certain occupations: accountants, engineers, and IT specialists, electricians, mechanics, welders, and tool and die workers, which are all detail oriented occupations. Then I began to notice that the genograms were showing these traits and occupations on both sides of the family. It was on my mind so much I even wrote a poem about it:

Thought’s Genogram

with lilacs. The last descendant.

So, I began to think that mating patterns might be a missing piece of the puzzle. I noticed that, in my practice at least, when ‘smart people married smart people’ (with ‘autistic traits’ in their family tree) the risk of autism went up. I was puzzled, however, because there was no research evidence to support this observation of mine. Then, very recently, research put this puzzle piece in place. A very large-scale, well done, research study on men in the Swedish military revealed that the smarter and more detailed oriented the men were, the more likely they were to have a child with autism7! There is a genetic term for this very modern phenomenon—positive assortative mating—defined as a form of sexual selection in which individuals with similar phenotypes (i.e. traits) mate with one another more frequently than would be expected under a random mating pattern.

To finish the puzzle, though, we would have to find one last piece by answering this question: Why is there more assortative mating? Are more people with ASD traits marrying each other? Here’s my working (i.e. not yet proven) hypothesis:

For the last 100,000 years, humans selected their mates within a very small group of hunter gatherers. As society evolved to living in small towns and farms, humans mated within the limited confines of those in the community. If someone lived in a traditional society, their parents arranged their marriages often to complete strangers. In none of these societies did one did pick one’s partner, but with the extraordinary mobility in all modern societies over the last 50 years (viz. over the time of autism’s steep rise), the number of eligible men and women traveling off to school and/or workplaces far from home has markedly increased the pool of mates to choose from. We tend, both statistically and naturally, to marry someone like ourselves—based on similar personalities and interests, similar intelligence and even traits—more than ever before in human history. Now we can even pick our mates, who can live anywhere in the world, by menu on dating apps!

In short, my working hypothesis is that the reason for autism’s dramatic increase, the missing puzzle piece, may be because of a relatively recent, large-scale change in the way we choose our mates due to a global increase in human mobility. This would be both an environmental and genetic explanation for autism’s rise. Not that it matters. I’m not suggesting that we are going to change how we pick our mates on a global scale.

I am saying that autism spectrum disorders reflect what is going on in society and society reflects what is going on with autism spectrum disorders.

Just to summarize: The steep increase in autism prevalence is still a puzzle but what’s clear is that the environmental contributors to autism’s rise are due to changes of highly developed societies—toxins, sophisticated medications, pediatric intensive care units, marrying at older ages, etc.; and the genetic characteristics of parents who have children with autism include smart, and detail-oriented people who work in technical and mechanical fields. Is it possible that the dramatic increase in autism has to do with the fundamental changes in the way we choose our partners in a highly advanced society? I look forward to more research into this question.

In the meantime, in this new series of blog posts, I will explore this theme of autism and society, of understanding human nature as seen through the lens of autism. And I start back at the beginning by empathically going inside the mind of the youngest children with autism in the next blog called The Beauty of the Line.